Who doesn’t love a good documentary? Anytime you go onto Netflix, you are bound to see hundreds of new, gritty, typically-murder-related real-life retellings that the entire world will spend hours upon hours greedily devouring. The stories are thrilling, shocking and typically end with a surprising yet neat conclusion that leaves the audience wanting more. This irresistible and seemingly limitless entertainment is so engaging it is easy to forget that these stories are based on real life and that once the documentary ends, the lives we have just become invested in, do continue, despite how they were presented. These experiences after their time in the limelight were captured and documented by Camilla Hall and Jennifer Tiexiera in their new documentary. Subject follows the dangerous effects documentaries can have, and how they can ruin people’s lives, a task deemed “extremely important” to the directors. The directors force the audience to confront the harsh reality of some of the most famous documentaries, and how we shouldn’t forget the human story behind the project.

The directors of Subject depicted their work as a “love letter to their community” of filmmaking, and the whopping 110 documentaries featured is a testament to this. However, despite the clear appreciation of their exceptionally wide field, it is the five case studies within Subject that really display the passion of Hall and Tiexiera. The majority of the film’s runtime dissects the lives of people involved in The Staircase, The Square, Hoop Dreams, The Wolfpack and Capturing the Friedmans, and the fallout for each of the individuals.

Unlike the documentaries themselves in which you get “sucked into the incredible storytelling,” this film feels very personal from the first scene in which Margie Ratliff (one of the daughters in The Staircase and a Co-Producer on this documentary) is read the terms of the consent form and she “sceptically” agrees. These individual’s lives are not over-dramatized but instead they, and their experiences with the documentaries they were involved within, are presented so truthfully an audience cannot help but feel uncomfortable at supporting something that brought these people so much grief over the years. Though this guilt is not the intention of the directors, it does force watchers to question the morality of other documentaries or true crime dramas they have watched recently.

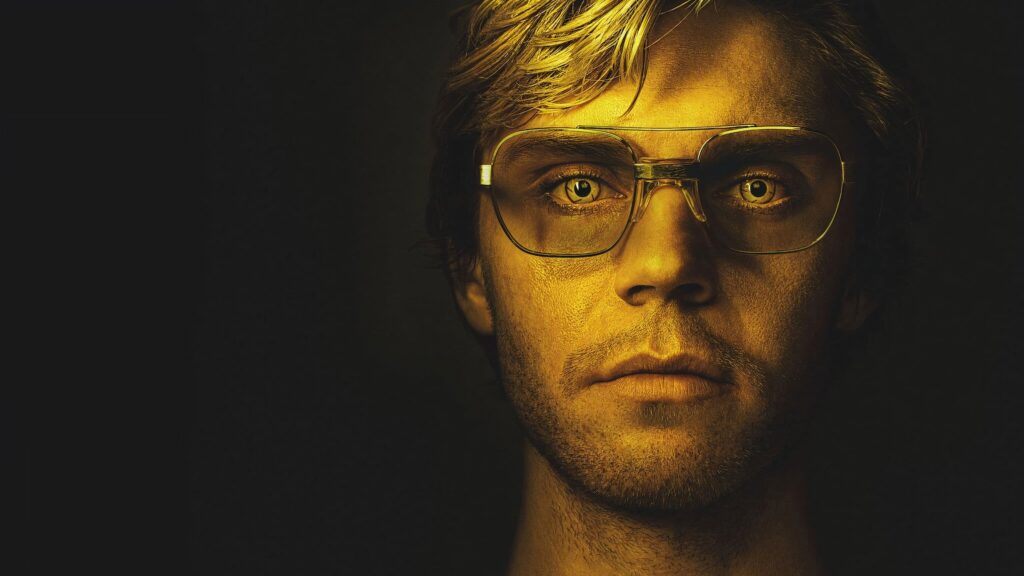

Netflix’s 2022 show Dahmer released to wide success among critics and audiences alike, yet the moral direction of the show is undoubtedly unclear. Though the show does present Dahmer as a villain, it also depicts him as a main character, which in turn leads to people believing him to be likable, or even attractive (some of the most cursed TikTok’s I have ever seen). By having such a focus on the killer, the victim’s stories are overshadowed and trivialised, belying the intention of directors when making these documentaries, to entertain rather than focus on the trauma and lives of those affected.

This is partially one of the reasons that the directors of the mentioned documentaries within Subject are not involved in the interviews, as it gives the participants more of a voice and creative say in how their story is presented. Hall and Tiexiera further utilised their documentary to bring light to other debates within the process, including responsibility due to the power of the genre, and whether or not people should be paid for their time and contribution. The most intriguing thing about the way these are presented is that they give room for the audience to make their own decisions about what is just, rather than piling on the directors perceptions to overwhelm you.

We have become conditioned when watching documentaries, engrossed with the “twists and turns” of the cases and satisfied once the show ends with a conclusion that wraps everything up into a neat little bow. However, Hall and Tiexiera reveal that this isn’t reality with their profound and stunning summary, in which they display the actual future of each of the “subjects” in the studied documentaries. Each character’s life is delved into and the haunting often tragic truth is revealed, with no frills. Some people have succeeded through their exploitation, yet a devastating number are struggling to get by. This ending summarises the bold strength of Subject as it doesn’t hold back and mask the heart-breaking reality.

This guilty feeling the film leaves viewers with is a daunting one, and it can make sense if some audiences are put off by this prospect. Additionally, this film does struggle a bit under its own weight, due to the amount of content they attempt to cover. Despite this however, I cannot recommend this documentary enough. The devotion and love in this project is clear and the five years it took to create appear to have been well spent. If anything, this film gives future audiences a better perspective about true crime documentaries, and how for the ‘subjects’ there is no neat ending once the cameras stop rolling.

4/5